Detectives have had a special niche in popular culture for many years. Beginning in the nineteenth century with the works of Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins and followed later in the century by Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes, detectives captured the nineteenth-century imagination. Today, crime novels, although still popular, have been supplanted by serialized crime dramas like the CSI and Law & Order franchises, and more recently by the revived Sherlock series and Luther. But where does this fascination with detection come from? Some have argued that the Victorians (and it certainly didn’t stop with them) had a keen enthusiasm for the macabre, whether it be executions, murders or other salacious tales of malice.[1] But it was not only the crimes that made headlines, it was the men who investigated them: professional detectives.

Bow Street police court

Formal detection in England began in mid-eighteenth century London with the Bow Street Runners. Begun by Bow Street magistrate Henry Fielding and continued under his blind half-brother John, the Runners were part of Fielding’s innovative approach to combatting crime. Since there were no centralized or professional police in England, the Runners were the first to systematize criminal investigation through information gathering. They investigated crimes for the government, helped private individuals, and even protected the royal family. Bow Street also had a series of mounted and foot patrols to police the city on regular beats. By the 1820s, however, the Runners’ reputation was in decline. Their legacy was tarnished by their association with thief-takers and they were known to collude with criminals to ensure the return of stolen property. Although effective, their methods were not as wholesome as the government would have wished and they were disbanded in 1839.[2]

The Bow Street Runners were an important forerunner to Scotland Yard’s detective force. Formed in 1842, shortly after the disbandment of the Runners and a horrific murder, the Detective Department was the first streamlined detective force in England. Given that the London Metropolitan Police (founded in 1829) was England’s first centralized police force, it made sense that the first police detectives operated in England’s, and Europe’s, largest city.

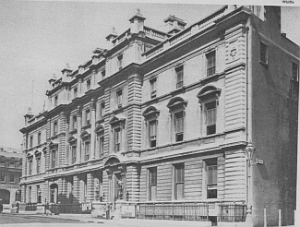

Old Scotland Yard (behind original location of the Metropolitan Police on Whitehall)

Scotland Yard’s detectives typically investigated serious felonies, especially murders. This is most likely because by the 1840s, the death penalty was only routinely applied for convicted murderers, and the government wanted seasoned officers to help investigate and prosecute those cases.[3] Such cases required flexibility in terms of time and location that regular police constables were unable to perform because they were restricted to their ‘beats’. To gain information, detectives made a habit of getting to know the criminal element in London, through frequenting pubs and races, employing informers and even using the newspapers to find information and discover possible frauds.

The Met’s detectives undertook inquiries assigned to them by the Commissioners of Police as well as undertaking investigative work for the Home Office, private individuals and institutions, and local magistrates. There were several sub-divisions within the detective department, with some men specializing in loan-office swindles, fraudulent betting, foreign inquiries, naturalization, and extradition cases. They also investigated political crime, guarded important figures of state, and kept an eye on foreign revolutionaries who fled their countries for safe haven in England. Detectives frequently undertook cases on behalf of foreign governments or institutions. In other cases, police detectives were asked to extradite foreigners back to their own countries, or to bring back English citizens from abroad on extradition warrants. Investigating forgery and coining offenses was also a routine detective activity.

Some of the men became quite famous. Charles Dickens took a shine to the first wave of detectives. He published interviews with them in his journal Household Words. He praised their talent for catching criminals, writing, “If thieving be an art…thief-taking is a Science.”[4] In his novel Bleak House, Dickens based the character Inspector Bucket on real life Detective Inspector Charles Frederick Field. Wilkie Collins also included a Met detective in one of his novels. Sergeant Cuff in The Moonstone was based upon Detective Inspector Jonathan Whicher. Both detectives are portrayed as intelligent, thoughtful and judicious men, albeit with a touch of mystery about them. The positive portrayal of police detectives by Dickens and Collins was a sea change in the way educated Britons perceived centralized policing. In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, centralized police were considered symbols of continental despotism. By the 1850s the police and detectives had proved their worth by maintaining public order during turbulent periods (it is notable that unlike most continental states, England did not have a revolution during the nineteenth century) and combatting and investigating crime.

The ‘Bobby’ remains one of the more beloved figures in English culture – an accolade the English police worked hard to earn. The perseverance of nineteenth-century English policemen and detectives in the face of public skepticism and, at times, outright hostility paved the way for future police organizations. The creation of Special Branch in the 1880s, MI5 in the early twentieth century and the explosion of domestic and foreign espionage organizations during the First and Second World Wars owe their pedigree to the first waves of English detectives at Bow Street and the Met.

Rachael Griffin

Rachael Griffin is a PhD candidate at The University of Western Ontario in Canada. Her thesis is entitled: “Detective Policing and the State in Nineteenth-Century England: The Detective Department of the London Metropolitan Police, 1842-1878.”

For further interesting blog posts and resources, please see Rachael’s blog at http://victoriandetectives.wordpress.com.

[1] The best recent work on the subject is Rosalind Crone’s Violent Victorians: Popular Entertainment in nineteenth-century London (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2012). Although less academic, Judith Flanders’ The Invention of Murder: How the Victorians Revelled in Death and Detection and Created Modern Crime (London: Harper Press, 2011) identifies the Victorian fascination with murder.

[2] J.M. Beattie, The First English Detectives: The Bow Street Runners and the Policing of London, 1750-1840 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012); David J. Cox, A Certain Share of Low Cunning: A History of the Bow Street Runners, 1792-1839 (Portland: Willan Publishing, 2010).

[3] Philip Thurmond Smith, Policing Victorian London: political policing, public order and the London Metropolitan Police (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1985), 18.

[4] Household Words, July 13, 1850.

** This post is the result of independent academic work and is intended for future publication by the author. Please do not reproduce the content of this blog in print or any other media without permission of the author (reblogs excepted). Any questions or concerns can be directed to Rachael Griffin via the Feedback page.

Reblogged this on Victorian Detectives.

LikeLike

Ms. Griffin,

Elsewhere I have read that, in 1839, 10 years after Scotland Yard was founded, the Bow St. Runners were absorbed into the Met.

Were they disbanded altogether, absorbed into the Met (like the River Police which is now the Met’s Thames Division) or something in-between?

LikeLike

Dear Jim,

Sorry for not seeing this earlier. I hadn’t realized that comments on this post didn’t come directly to me. Yes, they were absorbed fully into the Met, although some chose to retire. After 1839 the policing function of London’s magistrates ceased entirely.

Best wishes,

Rachael

LikeLike

“The creation of Special Branch in the 1880s, MI5 in the early nineteenth century and…” <– 20th century.

LikeLike