Section 1: Contextual Overview of the Development of the English Legal Profession

Before a full sketch of the history of the Training Contract can be drawn, it is necessary to provide a brief introduction to the development of the English legal profession as a whole.

From the mid-12th Century, there existed a Bench of learned men at Westminster who were an extension, and administrators, of the King’s justice and heard legal pleas. After a few decades, they decided to travel the realm and administer justice locally, and naturally their number grew.

The development of anything that could be called a ‘profession’ was exceedingly slow at this time because ancient principles such as a pleader having to appear and speak on his own behalf hindered anyone being able to speak for the pleader and therefore represent him. However, some representatives were permitted and a few select names began to appear regularly on the records of the King’s Bench.

At a very general level, in circa. 1250, there were two types of professional appearing, (1) a class of Serjeants at Law who presented the pleader’s case and responded to any argument that arose out of it, and (2) Attorneys who appeared on behalf of a claimant and spoke for him. The Serjeants’ workload became focused on appearing in court, whereas professional Attorneys handled the managerial, preparatory side of affairs. These broad distinctions developed over the centuries into what we now know as Barristers and Solicitors.

The profession was taking shape and the 1275 Statute of Westminster imposed penalties on lawyers who were found to be deceitful, an early sign of regulation. It took time for the above distinctions to be clarified through practice and throughout the 1300s there were a group of students that learnt the ways of the court, although they were not attached to any man in particular but to the Court itself.

In the 1400s, we see the word Solicitor specifically used and there was much work in the most used Court (the Common Pleas) due to the proliferation of litigation and increase in types of action; therefore the profession grew. The role of Attorney still existed but the two roles overlapped significantly, although the role of Attorney was not officially abolished until 1873.

Attempts were made in the 1500s to regulate this new branch of professionals but few regulatory inroads were built. From 1590 to 1630 in particular, certain judges attempted to eliminate the profession as it was seen as less honourable and gentlemanly than the role of Barrister. Their attempts failed and, in the early 1600s, Solicitors were most certainly a distinct profession in their own right.

Around this time, men began to operate as Solicitors in partnership with each other and as their businesses grew it became customary for new entrants to the profession to work and learn under these Solicitors, as ‘Articled Clerks’. These were effectively contracts that bound the Clerk to their master for a certain length of time. Certainly, by the 1630-50s, it was a strong convention that these Articled Clerkships had to be undertaken, but, as of yet, there was no regulation or law on the issue. It is at this moment that we can pinpoint the early beginnings of what are now known as Training Contracts.

Section 2: Specific Development of the Solicitors’ Training Contract

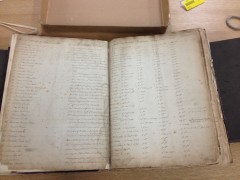

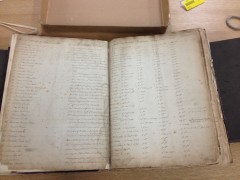

Things slowly and ponderously developed, as they always seem to along the winding path of English Legal History. Until the Attorneys and Solicitors Act 1728, it was not required by law that there be a central record of practicing Solicitors, however some Courts did keep Books of Attorneys for their own purposes before this time.

A record of the Attorneys practicing in the Court of Common Pleas. (National Archives)

The Act specified that after the 1st December 1730, no man could practice as a Solicitor unless his name was on the Roll, and significantly, no man could practice as a Solicitor unless he had undertaken an Articled Clerkship for at least a term of 5 years.

Further regulation came into place over the coming years, such as the Continuance of Laws Act 1748, which specified that Articled Clerks, on completion of their Articles, had to file a statement to this effect at the Court within 3 months. This time limit was later increased to 6 months.

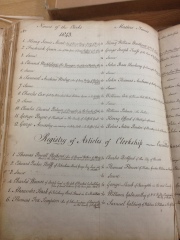

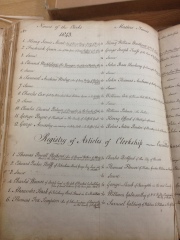

By 1843, pressure led to the reduction of the Articled Clerkship to a term of 3 years if you graduated from a degree at the Universities of Oxford, Cambridge, Dublin, Durham or London – as you were of a higher calibre. The 1785 to 1867 Register of Articled Clerkships shows the vast majority of terms being 5 years, but they are occasionally higher at 6 or 7 years and some at 3 years. One example recorded was for a mere 10 months.

A record of the mandatory registration of Articles of Clerkship. (National Archives)

In 1785, 129 Articled Clerkships (in the busiest court, the Common Pleas) were registered which we can contrast against the 4,869 Training Contracts registered with the Solicitors’ Regulation Authority in 2011. Please see some specific examples of Articled Clerkships in Appendix 1 to this post.

The Articled Clerkship continued to develop and began to generate additional complexities, exceptions and methods to ensure the quality of training involved was up to the high standards of a noble profession. In the Solicitors Act of 1860, it was established that if you worked as a de facto Articled Clerk for 10 years, you could enter the profession fully if you completed 3 years of a formal Clerkship. I believe this is the origin of the term known within the profession as ‘ten-year man’.

Around the same time as the 1728 Act, a group of Solicitors set up the ‘Society of Gentlemen Practisers in the Courts of Law and Equity’. This was the predecessor body of the Law Society, which was incorporated in 1826, and now deals with many aspects of regulating Solicitors. The Solicitors’ Regulation Authority, a subsidiary arm of the Law Society, now specifically deals with the regulation of Training Contracts. It was the early forms of these bodies that imposed high standards on Solicitors and led the profession to be seen on the same level as Barristers.

In 1877, further legislation made it a requirement that you had to pass exams set by the Law Society before being allowed admittance to the Profession, however exams had been carried out by the Law Society since 1836. By 1936; you were required to submit evidence of good character to the Law Society at least 6 weeks before starting your Articled Clerkship. As an interesting aside, the Solicitors (Articled Clerks) Act 1918 made provision for time spent serving in the war as counting towards the term of years of your Articles.

By the time we reach 1922, the starting point is that a 5 year Articled Clerkship is still required although terms of 3 or 4 years became more prevalent. At this stage, the Law Society required a mandatory academic year to be undertaken by Clerks, although many still solely qualified through Articles. The quality of training of an Articled Clerk was again emphasised in the Solicitors Act 1936 where it is specified that a Solicitor cannot take on a Clerk until they have practiced for at least 5 years themselves.

An Act of 1956 codifies for the first time a structure of what one must do to enter the profession of Solicitor. You must have (1) completed an Articled Clerkship (by this time commonly referred to as just ‘Articles’ or ‘Articles of Training’, (2) passed a course of Legal Education, and (3) passed the Law Society’s exams. Towards these ends, the 1965 Act grants the Law Society powers to create provisions regarding the education and training of those wanting to be Solicitors. The Training Regulations of 1970 specified that the longest time that could be served under Articles was 4 years, although if you were a law graduate, this was most commonly 2 years.

The currently in force 1974 Act allows for further Training Regulations to be created, in conjunction with the Secretary of State. The transition between the 1989 and 1990 edition of the Training Regulations changed the term ‘Articles of Training’ to that of ‘Training Contract’ in an attempt to use simpler and clearer language. The term of years in those regulations is set at 2 years. It has been called a Training Contract since 1990 and the very detailed Solicitors’ Regulation Authority Training Regulations 2011 are the provisions that currently govern it.

There is currently a consultation being conducted by the Solicitors’ Regulation Authority named ‘Training for Tomorrow’ which may significantly change the rules and procedures relating to Training Contracts. This consultation finishes on the 28th of February 2014 and we can only wait and see where the Legal History of the Training Contract will develop next.

NB – Information in the below Appendices can be used but only if credit is given to this Blog. Recommended citation: Ben Darlow, ‘History of the Solicitors’ Training Contract’ <link to this blog post> accessed [day] [month] [year]

Appendix 1: Examples of Articled Clerkships in the Court of Common Pleas between 1785 and 1867

- Fiennes Wykham – Clerk to Richard Bignall of Banbury – Articles dated 12th July 1785

- Thomas Berryman – Clerk to Samuel Plaisted of Bernards Inn, London – Articles dated 16th October 1788

- William York Jr – Clerk to William York Snr of Thrapston, Northampton – Articles dated 27th November 1800

- Michael Kennedy – Clerk to Edward Codd of Kingston-upon-Hull – Articles dated 10th November 1817

- Thomas Powell Watkins – Clerk to Charles Bedford of Worcester – Articles dated 4th November 1843

- Fred John Wise Jr – Clerk to Fred Wise Snr – Articles dated 8th July 1865

An example page from the Register detailing the names of Clerks, their masters and the term of years. (National Archives)

A page of the Register showing various terms of years of the Clerkships. (National Archives)

Transition page when the Solicitors Act 1843 was introduced. (National Archives)

*Observation – from the register of approximately 9,500 Clerks in this 82-year period, approximately 1 in 5 are Articled to their father.

*Observation – unfortunately, the earliest Register of Articled Clerkships, between 1713 and 1837 is mould damaged at the National Archives.

Appendix 2: Examples from the Roll of Solicitors admitted 1729 to 1788

- John Applegarth – admitted to the Roll on 8th July 1729 – Examined by Mr E. Probyn

- John Forrest of Middlesex – admitted to the Roll 3rd July 1729 – Examined by Mr R. Raymond

- Benjamin Holt of Hereford – admitted to the Roll 28th June 1729 – Examined by Mr E. Probyn

- Samuel Plummer of London – admitted to the Roll 27th June 1729 – Examined by Mr R. Raymond

- John Darrell of Cheshire – admitted to the Roll 14th June 1788 – examined by Mr Ashurst

*Observation – the register contains approximately 7,600 solicitors admitted to the Roll over this 60 year period.

The cover page from the Roll of Attorneys 1728 to 1788. (National Archives)

Examples from within the Roll of Solicitors. (National Archives)

Appendix 3: Oath required by the Attorneys and Solicitors Act 1728 to be admitted onto the Roll of Solicitors

“I [Forename][Surname] swear that I will truly and honestly demean myself in the practice of an Solicitor, according to the best of my knowledge and ability. So help me God.”